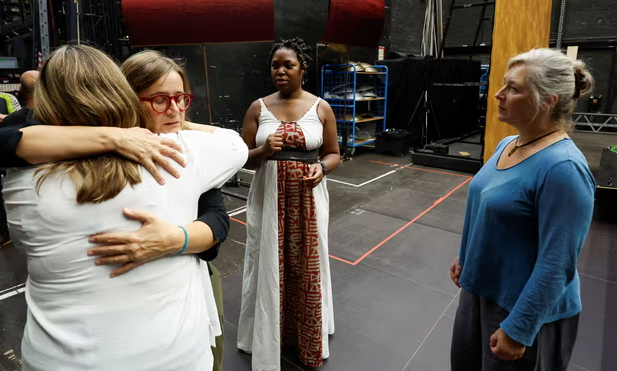

The operatic version, due to open this week at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, is among the first in Europe to have worked with an intimacy coordinator in an effort to ensure performers are comfortable as they tackle scenes that include everything from touching to kissing and caressing.

The idea of bringing in a consultant to focus on intimacy was initially questioned by the show’s producers, said Ita O’Brien, the intimacy coordinator who worked on the production. “There was a bit of a thing, going: ‘We haven’t had this before and we don’t really think we need it,’” she said.

It was a line familiar to O’Brien, who has advised HBO and Netflix productions and long advocated for the profession.

“It’s the same as choreographing a waltz or a tango or choreographing a fight. It is a body dance,” she said. “But you’re asking two people who aren’t in love with each other, who don’t necessarily know each other, to form this amazing body dance of intimacy.”

While few would question the need to bring in choreographers for a dance or fight scene to mitigate the risk of injury, she said the stakes were higher when it came to performances that included intimacy. “The injury could not only be physical but emotional and psychological.”

O’Brien’s pioneering role in Barcelona comes months after Spain’s football chief planted an unsolicited kiss on a World Cup-winning football player, catapulting the country into a reckoning on sexism, consent and abuse of power in the workplace.

The conversation gave rise to a hashtag – Se Acabó, or “it’s over” – as it snowballed into a #MeToo moment for Spanish football.

O’Brien said she was added to the Antony and Cleopatra production team after working with the soprano Julia Bullock during last year’s Royal Opera House production of Theodora. The initiative – a first for Britain – introduced O’Brien to the complexity of working with operas.

Some of these challenges were physical, she explained, citing the need to find positions that are comfortable for performers while still allowing them to make “amazing sounds”.

Others required an overhaul of working styles, she said, pointing to opera’s history of flying in cast members days before a show begins.

“They would literally have two days to stage it,” she said. “So you stand there, you walk there, you drink a glass of wine there, you kiss her hand there, you have sex there and you rape her there, blah blah blah, OK great, on you go.”

The approach put performers at risk, with some left feeling awkward, harassed or abused, she said. “You can imagine that there’s no time and space for agreement and consent.”

It was the wider #MeToo and Time’s Up movement that helped pave the way for intimacy coordinators to become a staple on sets around the world, O’Brien said. “That’s when the industry’s going: ‘You are now being listened to and heard and we cannot turn a blind eye to this behaviour any longer.’”

Allegations of sexual harassment have also rocked the opera world. At least 20 women have accused the Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo of kissing, grabbing or fondling them in incidents dating back to the 1980s. Domingo has denied any wrongdoing.

O’Brien described her work as part of a broader shift gripping the industry, one that was challenging the longstanding notion that the show must go on at all costs.

“The shift is going: ‘This is our workplace – our rehearsal room, a performance on stage is our workplace,’” she said. “And just like anybody in our workplace, we should be able to work without fear of harassment and abuse.”

More . . .

RSS Feed

RSS Feed